Communities as Health Systems: Treating Malnourished Children

DATA

A steadily growing body of evidence from NGOs and nutrition researchers challenges conventional wisdom on treating children with severe malnutrition

IMPACT

The lives of hundreds of thousands of children worldwide have been saved through community-based treatment with nutrient-rich foods

Photo: Elizabeth Whelan, “Untitled,” Segou, Mali. Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license obtained; available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0. Used with permission.

Acute malnutrition, also called wasting, occurs when children rapidly lose weight due to lack of food or serious illness. Severe wasting is traditionally treated in clinics and hospitals, but in many countries the large majority of afflicted children do not receive care. In the last 15 years, nutritionists have developed protocols for community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), wherein 80 percent of children – those without complications – can be treated at home with specially formulated nutrient-dense foods. The mounting evidence on the performance and cost-effectiveness of CMAM is propelling reform of nutritional treatment protocols in dozens of countries worldwide.

The Cost of Wasting

Over half a million children die every year from severe wasting.1 Until recently, wasting was treated in health facilities and special feeding centers, but this approach has major disadvantages: only a small fraction of wasted children are reached, infection spreads easily among immunosuppressed patients staying in facilities, and parents have to spend weeks away from home waiting for children to recover.2

The Trailblazers

Steve Collins, Kate Sadler, and the NGO Concern Worldwide developed CMAM as an alternative treatment model in the early 2000s.3 Pilot projects in Ethiopia, Malawi, and other countries showed that 80 percent of wasted children can be treated effectively at home with ready-to-use therapeutic foods – candy bars and nut butters packed with nutrients to safely and quickly nurse wasted children back to health.4 New ways of screening for malnutrition, especially the use of simple bands to measure upper arm circumference (see photo on first page), allow communities to diagnose wasting themselves, further increasing the number of children identified for treatment.

CMAM Becomes the Standard

The international medical community was initially slow to accept CMAM, wary of treating very sick children outside formal facilities. However, governments and humanitarian NGOs, faced with overwhelming caseloads, took the lead. Soon data about the impact of CMAM began to pour in from dozens of projects. In 2007, the United Nations gave its formal approval, releasing official CMAM protocols.5 Research on the impressive cost-effectiveness of CMAM further bolstered the case.6 7 Today, over 40 countries have drafted wasting treatment guidelines in which CMAM is a key component.

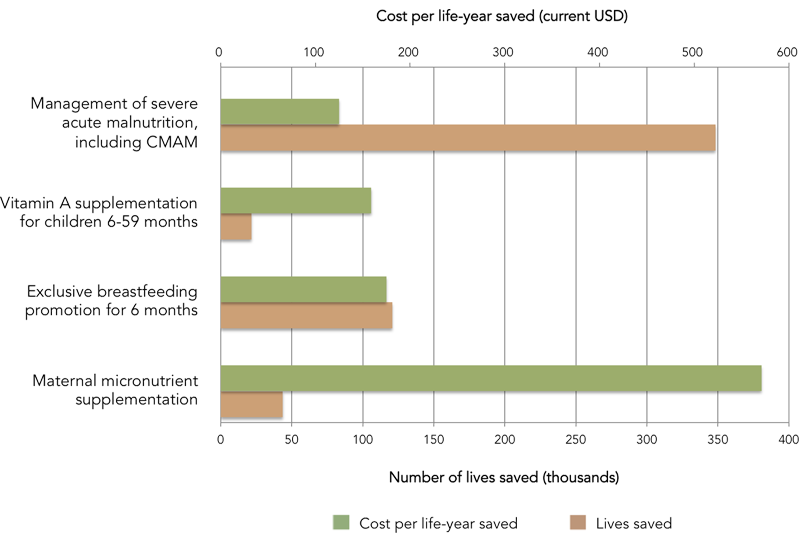

Number of lives saved and cost per life-year saved for major nutrition interventions. Management of severe acute malnutrition, with community based approaches as an important element, saves the most lives and costs the least per life-year saved. Source: Bhutta et al. 2013

Image: Adapted from Bhutta, Zulfiqar A, Jai K Das, Arjumand Rizvi, Michelle F Gaffey, Neff Walker, Susan Horton, Patrick Webb, et al. 2013. “Evidence-Based Interventions for Improvement of Maternal and Child Nutrition: What Can Be Done and at What Cost?” The Lancet 382 (9890): 452–77. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4

References

1. Black, Robert E, Cesar G Victora, Susan P Walker, Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Parul Christian, Mercedes de Onis, Majid Ezzati, et al. 2013. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries.” The Lancet 382 (9890). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

2. Collins, Steve, Nicky Dent, Paul Binns, Paluku Bahwere, Kate Sadler, and Alistair Hallam. 2006. “Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Children.” Lancet 368 (9551): 1992–2000. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69443-9

3. Collins, Steve. “Empowering Communities to Tackle Malnutrition.” 2015. State of the World’s Children 2015: Reimagine the Future. http://sowc2015.unicef.org/stories/empowering-communities-malnutrition/ (accessed April 17, 2015)

4. Collins, Steve, Kate Sadler, Nicky Dent, Tanya Khara, Saul Guerrero, Mark Myatt, Montse Saboya, and Anne Walsh. 2006. “Key Issues in the Success of Community-Based Management of Severe Malnutrition.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin 27 (3 Suppl): S49–S82.

5. World Health Organization (WHO), World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition (SCN), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2007. Community-Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/Statement_community_based_man_sev_acute_mal_eng.pdf

6. Bachmann, Max O. 2009. “Cost Effectiveness of Community-Based Therapeutic Care for Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition in Zambia: Decision Tree Model.” Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 7 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-7-2

7. Wilford, Robyn, Kate Golden, and Damian G Walker. 2012. “Cost-Effectiveness of Community-Based Management of Acute Malnutrition in Malawi.” Health Policy and Planning 27 (2): 127–37. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr017