Cash Transfers in Humanitarian Emergencies: Data vs. Politics

DATA

Analysis of historical and modern food emergencies argues for the use of cash transfers to help the hungry

IMPACT

Major NGOs and European donors have reoriented their humanitarian response impact strategy to emphasize cash transfers, and the US has passed incremental reforms

Photo: Elizabeth Whelan, “Untitled,” West Godavari, India. Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license obtained; available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0. Used with permission.

For decades, the US government used food aid as the primary means to address hunger in humanitarian emergencies. Shipping companies, NGOs, and agribusiness interests all profited from the food aid system and lobbied strongly to maintain the status quo. In the past two decades, however, a large body of data shows that where markets are functioning, cash transfers are a more effective form of aid, allowing families to determine their own spending priorities and stimulating the local agricultural economy. As a result of this research, governments and NGOs worldwide are shifting to cash for emergency response.

The Foundations of Reform

In the 1980s, the economist Amartya Sen used historical famine data to show that hunger in the modern world is less a problem of insufficient agricultural production than the inability of families to purchase food due to high prices, lack of cash, and poorly functioning markets.1 The work of Sen and others suggested that injecting cash into local economies not only gives people purchasing power, but also encourages regional farmers with grain surpluses to sell their crops in areas of food deficit.

The Weaknesses of Food Aid

The critique intensified in the late 1990s and 2000s. Researchers from universities, think tanks, and NGOs all over the world identified the key problems of the food aid approach: shipment costs consume much of aid budgets, shipping delays lead to emergency needs being unmet, and the introduction of foreign grain undermines incentives for local agricultural trade.2

The Status Quo Begins to Shift

From over a hundred studies on the performance of cash transfers in emergencies compelled several large NGOs and some European donors to reevaluate their aid strategy.3 4 5 The US government recently proposed food aid reforms that would allow present levels of assistance to reach 2 to 4 million more people by saving $105-165 million every year, and recent legislation took steps towards improving the flexibility of spending in the aid system.6 7 8 The trend towards a more data-driven approach to humanitarian response has been slow but unmistakable.

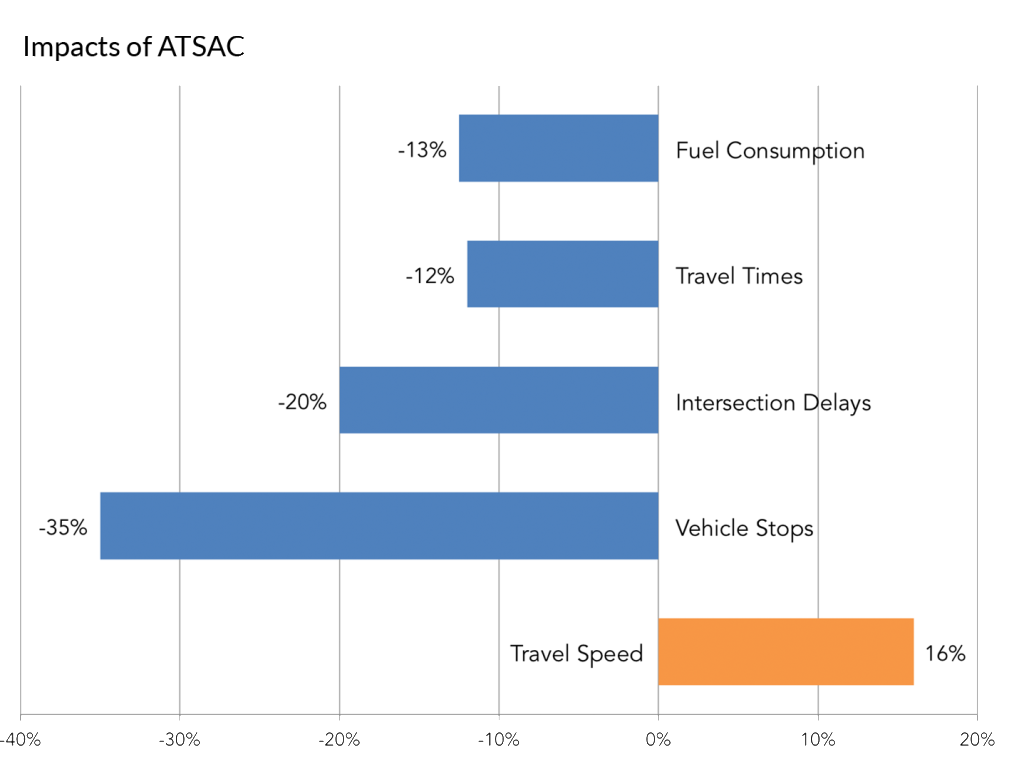

Graphic: From Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2014. “Creditor Reporting System.” OECD StatExtracts.

References

1. Sen, Amartya. 1981. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2. Barrett, Christopher and Daniel Maxwell. 2005. Food Aid After Fifty Years: Recasting Its Role. New York: Routledge.

3. Harvey, Paul. 2007. “Cash Based Responses in Emergencies.” Humanitarian Policy Group Report 24. London: ODI.

4. Bailey, Sarah, and Paul Harvey. 2015. “State of Evidence on Humanitarian Cash Transfers.” Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Background Note. London: ODI.

5. Department for International Development (DFID) Policy Division. 2011. “Cash Transfers: Evidence Paper.” London: DFID.

6. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). 2014. “Food Aid Reform: Behind the Numbers.” Washington DC: USAID.

7. Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79). 2014. “Section 3002–Set-Aside for Support for Organizations Through Which Nonemergency Assistance is Provided.” Enacted February 7, 2014.

8. Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (P.L. 113-76). 2014. “Division A, Title VII–Food for Peace Title II Grants.” Enacted January 17, 2014.